The Proper Use of Quotes

February 17, 2022

The simple quotation mark has a surprisingly long and rich history.

Its origin dates back a lot further than one might think.

While the practice of using a written symbol to indicate an excerpt from another written work dates all the way back to Ancient Greece, documented history informs us that the ancestors of the double quotation mark that we use today first appear in the margins of fifteenth-century manuscripts as annotations that bestow higher importance on the passages beside them.

Over the 400 or so years that followed this debut, the quotation mark experienced a slow evolution that saw changes in shape, curvature, relative height, axial orientation, and meaning.

While it’s debatable that their appearance continues to evolve to this day, considering that designers create new fonts every year, quotation marks in their modern manifestation exist to do essentially just three things:

- 1. To indicate a quotation from another written work or to quote the direct speech of real people or fictional characters.

- 2. To cite the titles of shorter literary or musical works like chapters in a book, episodes of a series, or songs from an album.

- 3. To highlight the irony of a word or phrase in context or imbue it with sarcasm.

Is it ever really that easy, though?

The simplicity of this three-item list hides all manner of exceptions, unique circumstances, and nuance. If anything related to quotes is easy, it’s how easily they are misused or even abused.

The literary consequences of a couple of errant quotation marks can be dire. The improper placement of the seemingly simple quotation mark can massively change the meaning behind a written statement.

Sign-makers—professional and amateur alike—are notorious for their apparent predisposition towards the gratuitous inclusion of quotation marks in their work, and the fruits of their labor are often quite hilarious.

The following guide aims to refresh your quoting know-how by laying out the basic rules of quotation and covering the various uses for quotes in written documents. It will also delve into style considerations.

In other words, by reading the rest of this blog, you’ll fortify your future work against an unsolicited appearance on this one.

Quoting Spoken or Written Words

At their core, quotation marks are for indicating to the reader that the words they are about to read are not the words of the writer…kinda.

While all the words in a work of fiction are the author’s words, a novelist uses quotation marks to differentiate between the various lines of dialogue and the narration.

Properly formatted quotation can bring a story to life and keep it flowing, but quotes are a matter of grave importance when it comes to other kinds of writing.

Quotes are especially important to non-fiction writers like historians, journalists, and academics. Quotes enable them to borrow the words of another—whether they are spoken or written—to support their idea, their argument, or the larger story they are attempting to tell.

An objective reporter can use quotes from various witnesses, participants, or officials to further illuminate the current event they are reporting on.

The subjective writer behind an opinion piece might use the quotes of another to support the stance they hold on a matter.

A student crafting a thesis statement can borrow the words of established writers or experts in a particular field to back up the claim they’re making.

So, how do they do it without getting slapped with charges of libel or plagiarism?

We’ll start at the very beginning.

Let’s say a guy named John Smith once said or wrote something regarding his feelings toward cauliflower and you wanted to quote him on it. Let’s try putting his exact words into quotes:

“I hate cauliflower.”

That doesn’t really cut it. You need to attribute the quote to someone:

John Smith said, “I hate cauliflower.”

With that, you have a perfect, basic, direct quote. Or, if you prefer, you can flip it around:

“I hate cauliflower,” John Smith said.

The sentence in either orientation informs the reader that the quote was spoken as opposed to written, and the quote is attributed to the speaker who uttered the words within the quotation marks.

It is also possible to quote a speaker without quotation marks:

John Smith said that he hates cauliflower.

This is known as an indirect quote. While the sentence relays the exact same information as the previous example without embellishment—and it maintains the emotional level of John’s disdain for cauliflower—it does not use the actual sentence that John spoke. Therefore, it does not require quotation marks.

Paraphrasing is another matter and it should not be confused with indirect quotation. Paraphrasing is when there is a reference to a spoken quote or a written passage and its sentiment is accurately captured, but there is no claim to any quotes in the retelling:

John Smith once told me about his feelings towards cauliflower. I don’t remember exactly how he put it, but he’s definitely not a fan of that particular vegetable.

Capitalization and Punctuation

When dealing with quotes, the rules of capitalization and punctuation are a matter of great importance as well.

If they are misplaced or ignored, it’s not only bad form, but it can confuse your reader and throw them off course.

Just as with a regular sentence, a sentence quoted in full should begin with a capital letter—even if the quote appears within the sentence that houses it:

John looked up at me and said, “Man oh man, cauliflower is really gross.”

A quote broken up part of the way through is known as an interrupted quote. With interrupted quotes, the second part of the quote is not capitalized:

“Man oh man,” said John while looking up at me, “cauliflower is really gross.”

As you can see in the example above, a comma follows the statement that indicates the speaker of the quote, and one is placed within the first half of the interrupted quote.

Also, take note that the period is placed within the closing quotation mark when the sentence concludes with a quote.

If you choose to quote only part of the sentence, the sentence fragment should not begin with a capital letter:

John called the cauliflower “really gross” before throwing it to the floor.

The placement of question marks in or outside of quotation marks depends on the context of the sentence:

John asked them, “What is it with you guys and this obsession with cauliflower?”

Does John always react like that whenever anyone says, “Let’s all have literally nothing but cauliflower for dinner”?

While rare, alternate punctuation outside of the quotation marks may be necessary in certain circumstances:

John often ranted about what he called cauliflower’s “Three Evils”: its appearance, its smell, and its taste.

Mr. Smith happily sampled all the vegetable dishes that were “not white and weird”; he ignored the various cauliflower casseroles.

Quotes within Quotes

It might sound like the setup to a brainteaser, but as a writer, sometimes you have to quote someone who quoted someone else in their own quote—maybe it’s a bit of a tongue-twister too.

To execute a successful secondary level of quotation, the single quotation mark is all you need:

Phil asked, “Did John really scream, ‘Get that cauliflower away from me’?”

If you’re looking for the single quotation mark on your keyboard, it’s located right beneath the double quotation marks that we’ve already been working so hard. You might know it as an apostrophe, but don’t worry, when it comes to flipping it the right way your computer will know just what to do.

Block Quotations

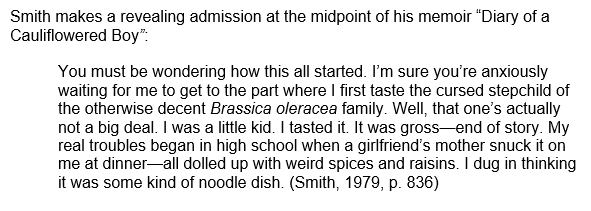

Block quotations come in handy when literally all the words in a particular passage from an author’s work are just so good that you feel as though you’d be doing a disservice to your reader by not sharing every last one of them.

Students and researchers often make use of block quotations when supporting a claim in an academic paper or a nonfiction manuscript.

Block quotes differ from the kinds of quotes we’ve discussed so far because, well, they’re way longer and they look like blocks.

You can’t just slap a long passage in between a pair of quotation marks and call it a day. There are certain rules you have to follow, depending on whom you’re writing for, and proper block quotes look pretty cool anyway.

So, let’s give one a go:

As you can see above, block quotations don’t use quotation marks at all. Their indentation is ½ inch further in and a line below their introduction. Finally, they conclude with a citation.

Style guides differ, but generally, if a typed-out passage takes up more than a few lines on the page, it should be presented in the form of a block quotation.

For questions regarding the proper format and citation styles of block quotes according to the most commonly followed manuals, consult this helpful visual from The University of Arizona.

Alternate Uses

While italics are used for citing or referencing larger works, quotation marks are used for citing shorter portions of them:

“Looks like Brains” is the worst song on John Smith’s independently released folk album Cauliflowernication.

Single quotation marks can be used in place of parentheses when translating an italicized foreign word within a sentence:

The injured German waiter said that all he did was offer the mysterious man some blumenkohl ‘cauliflower’ just before the assault occurred.

Scare quotes or shudder quotes are arguably the most fun kind of quotes, but as one can see from the examples linked at the beginning of this article, they should be used sparingly and with extreme caution.

Scare quotes paint the words between them with anything from irony to sarcasm to disdain, and it’s up to the reader to determine their meaning from context. Essentially, scare quotes indicate that the words they encapsulate do not actually mean what they usually mean.

A couple of examples based on what we’ve come to understand about John Smith:

Tonight, we’re having ham, mashed potatoes, and John’s “favorite” side dish: cauliflower.

A great way to “thank” John for totaling your car would be to sneak a whole head of cauliflower into his pillowcase.

Dialogue

We’ve already demonstrated how to properly frame a line of spoken dialogue, how to tag the speaker, and how to interrupt it with action.

When you’re dealing with multiple lines of dialogue—like when two fictional characters in a novel speak to one another—following a set of guidelines will make the conversation flow naturally for your reader.

Beyond the quoting rules that we’ve already covered in this blog, there are a few more we should go over when it comes dialogue:

New Speaker, New Paragraph. Whenever a speaker begins speaking, his or her words get their own paragraph—even if their line is just a single word. The act of making each line its own paragraph indicates to the reader that a new speaker is speaking.

Indentation. Each new “paragraph” (scare quotes!) of dialogue should be indented unless the quote itself is the beginning of a new chapter in a book or a new scene in the story.

Speeches. In the rare event that a character speaks for so long that their words flow into multiple paragraphs—like when one character is telling a long story or literally delivering a speech—leave off the end quotation at the conclusion of one paragraph but start the next one with another opening quotation mark.

Em Dashes. An em dash (one of these guys —) is a great way to represent one character cutting off the words of another with an interruption.

For this one, maybe a demonstration is in order:

“Come out on the veranda,” Lindsey beckoned, “I’ve prepared a glorious vegetable spread with multiple dips!”

“But I thought I told you that if I even see a cauliflow—”

“Say no more John,” she reassured him, “I’ve banned them entirely from the property.”

Clarity

When quoting spoken words or written text, getting them right is a matter of utmost importance.

Occasionally, when endeavoring to insert quotes into a document, you’ll encounter misspellings, poor grammar, or tenses that don’t match the one you’re working with. Luckily, there are workarounds for such a scenario.

When a misspelling or grammatical error is discovered, the ethical practice is to preserve it, but you wouldn’t want anyone to think that the error was your own. This is where brackets come to the rescue:

“Johnny Boy hated collyflower [sic] even when he was little.”

Placing sic (Latin for “thus” or “so”) italicized and between brackets is how you can indicate to the reader that you transcribed the quote exactly as you found it—warts and all.

Brackets are also a way to provide the reader with information they wouldn’t have otherwise. Using the same sentence, we’ll inform the reader that “Johnny Boy” is a nickname for a character we’re already familiar with:

“Johnny Boy [John Smith] hated collyflower [sic] even when he was little.”

Brackets are also at your disposal if you need to change a word in a quote so that it fits properly in your sentence.

If John Smith once said:

“My aversion to cauliflower has always been a problem for me.”

You could (if absolutely necessary) quote him like this:

John Smith’s aversion to cauliflower has “always been a problem for [him].”

Conversely, you may need to remove words from quotes entirely so that any off-topic information contained within them doesn’t confuse the narrative.

For example:

“Whole Foods is a store with delicious hot bar offerings and a wide selection of coffees from around the world, but it’s also a purveyor of cauliflower.”

With an ellipsis (three periods separated by spaces), we can shorten the quote to align with our topic while letting the reader know that unrelated words were removed:

“Whole Foods is . . . a purveyor of cauliflower.”

Presuming what follows is more negativity towards cauliflower, omitting the complimentary remarks about Whole Foods doesn’t change the overall sentiment of the sentence.

On the other hand, misquoting someone is at best a careless mistake requiring a correction or retraction; at its worst, a purposeful misquotation is a malicious act and grounds for a defamation lawsuit. If you handle your quotes with care and diligence, you won’t ever find yourself in either situation.

Style

One might think a literary practice so constrained by rules wouldn’t have any room to spare for personal style choices.

But when it comes to quotes, it’s in there.

With quotes, you can choose how to quote, what to quote, and how often to quote.

You can even choose how to attribute quotes.

For more wisdom on the matter, we reached out to Barbara Adams, a knowledgeable (and stylish) copywriter with The Writers For Hire:

“I have a degree in journalism,” Ms. Adams warned us at the outset, “so that definitely influences how I use and think about quotes.”

Warnings of journalistic bias aside, Ms. Adams was quick to dispense some pretty universal advice for writers of all breeds:

“Quote length is important,” she says. “My experience is that some writers struggle with how to introduce a quote, so they just dump a long quote in place. It would be better to summarize what the speaker is saying and then use the most important/cogent idea as the actual quote.”

Despite the fact that we may have already ignored her advice by just dumping rather than summarizing the very quote in which she gives the advice, what Ms. Adams said next was so poignant and perfect we felt it deserved its own block quotation:

Coming from a journalism background, I have no problem with using “said” or “says” over and over. I know some writers like to use other words – exclaimed, pointed out, noted, etc. – but I feel those should be limited to books (fiction or non-fiction). I write a lot of trade articles and using anything other than said or says (or “added”) would be completely out of place. I recently read a piece where there were a ton of quotes, and each had a different verb attached and it was just jarring. It was like the writer had done everything he could to avoid using “said” and got the thesaurus out, instead.

Sometimes it’s a classy move to conclude a written work with a quote.

Just in case this is one of those times, that’s how we’re going to end this blog entry.

The following is a pretty good quote that Ms. Adams gave us when asked if she had any quotes…about quotes. Plus, it gives us the chance to use brackets:

“[Quotes are] indispensable for adding color, personality and context to an article, but they also serve another, more practical purpose: they break up grey columns of copy.”