The ABCs of RFPs

June 22, 2017

New to proposal writing? It helps to learn the language.

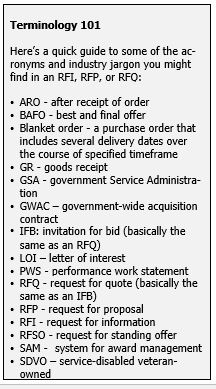

If you’re new to the world of proposals, it’s all too easy to get lost in a sea of acronyms, industry jargon, formatting rules, and submission guidelines. What’s the difference between an RFI and an RFP? How do you respond to an RFQ? What is a SOW? Is your company a WOSM or an SDVO? When do you send an LOI? And WTH (what the heck) is SAM?

This quick guide will help you decipher and make sense of some of the most common RFP lingo.

The major difference here is the length, the type of information, and level of detail you’ll need to provide in your response.

An RFQ — or request for quotation is all about the bottom line. When an organization sends out an RFQ, they know they want certain products or services delivered over a certain time period — and they’re looking for a vendor who can provide those products

or services for the best price.

Note: an RFQ is essentially the same as an IFB, or “invitation for bid” — don’t let the names throw you off. They’re asking for the same thing.

An RFI — or request for information — is like a mini-RFP. Organizations often put out RFIs as a way to gather big-picture information and answer questions that will help them refine their search, more clearly define their needs, and vet potential vendors. The RFI process is a little like speed-dating in that it offers a quick, no-commitment way for organizations and potential vendors to get a feel for each other, decide if they want the same things, and figure out if there’s potential to take things to the next level.

At this stage in the game, it’s all about the big picture. If your organization receives an RFI, you’ll probably be expected to provide the following information:

- A company overview that includes things like how long you’ve been in business, any certifications, licenses, or awards you’ve received, and your areas of expertise

- A company org chart, plus bios and/or resumes for your key personnel

- A general budget/cost estimate

- References and/or case studies from similar jobs and clients

An RFI response is typically much shorter than an RFP response — and in some cases, there may even be a maximum page count. Responses should be clear, concise, well-written, and not too wordy.

An RFP — or “request for proposal” is the largest, most detailed, and most comprehensive of the three. A typical RFP combines elements of an RFQ and an RFI, plus specific information about the scope of work (SOW) and the vendor’s ability to perform the work or provide the services outlined in the SOW. When you respond to an RFP, you should be ready to answer detailed questions about everything from your company’s hiring and staffing processes to technology and security measures to your financial standing.

In addition to answering questions, you’ll likely need to provide documentation such as:

- A letter of credit from your bank

- Proof of insurance coverage

- Employee training materials and documentation

- An implementation plan and a transition plan

- Case studies and/or letters of reference from previous or current clients

Depending on the organization issuing the RFP, your response could vary in length from 50 pages to well over 100. In addition to ensuring that you’ve answered every question and responded to every item on the RFP, you’ll also need to make sure that you follow formatting instructions to the letter and leave yourself time for proofreading and fact-checking before the deadline.

Note: In many cases, the issuer of the RFP will require that vendors send a letter of interest (LOI) before responding to an RFP. An LOI is a simple, to-the-point letter that formally announces your intention to prepare and submit a proposal.

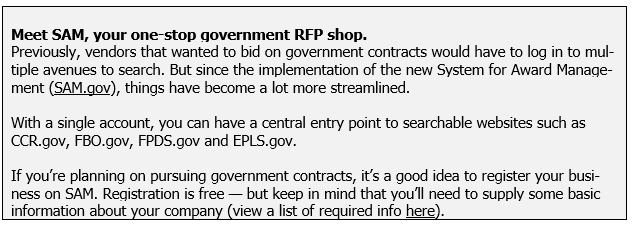

Public and private companies and nonprofit organizations typically send RFPs and RFIs directly to a pre-selected list of vendors. Government agencies, however, are required to publicly issue RFPs to ensure a fair and transparent bidding process (this is especially good news for smaller or younger companies who may not have the name recognition necessary for private invites).

If you’re looking for opportunities, check out your local city or state government websites. You can also use searchable databases that compile and maintain lists of open government RFPs.

Not sure where to look? Here are a few starting points:

- The Request for Proposal Database. This free, searchable site lets you browse hundreds of government and nonprofit RFPs in the U.S., Canada, and Europe. You can search by the type of service needed, and by location, and you can even pick up a few tips for crafting a winning proposal.

- Federal Business Opportunities. Search federal contract opportunities worth $25,000 or more. If you’re new to the site (or to the RFP process in general), be sure to check out their handy user guides.

- GovernmentBids.com. Search more than 35,000 RFPs and opportunities sorted by category and state. The best part of this site? You can also sign up for free email alerts customized to your industry and location, which means you’ll never miss an opportunity.

- GSA Acquisition Gateway. Although this site is primarily aimed at helping government agencies find qualified vendors and services providers, it does have some pretty great resources for vendors. And be sure to check out their related site, the GSA Vendor Support Center for even more tools and information.

Small business set-asides

If you’re a small business owner, you’re likely aware of the government’s small business set-asides, which helps ensure that small or under-utilized businesses have the opportunity to bid for — and win — government contracts. Some set-asides are open to all small businesses, and others are reserved for businesses that fit certain criteria or hold specific certifications, such as:

- 8(a) Business Development: This program is for companies that are at least 51 percent owned and operated by socially and economically disadvantaged people.

- HUBZone Program: This program encourages economic development in historically underutilized business zones.

- Women Owned Small Business (WOSB) Program: This program is for small businesses owned by women.

- Service Disabled Veteran Owned (SDVO) Program: This program is for businesses owned by disabled veterans.

If your organization fits into any of these categories, you may gain a small advantage. It’s definitely worth a look.

A final note on this: If you want to see a (darkly) funny take on small business set-asides, check out the 2016 film, “War Dogs.” Based on a true story, the movie follows a pair of gun dealers who pursue government weapons contracts through small government set asides.

Ready to get started?

We could, quite literally, write a book about RFPs. Several books, probably.

The learning curve required to write a winning proposal — combined with the often-intimidating list of required materials and documentation — can be a bit intimidating even if you’ve been through the RFI or RFP process a few times.

That said, the process of crafting a solid, well-written proposal does get easier — especially if you know the lingo.