Characters in Your Clan? Write a Family History Book with Personality

March 20, 2025

No one wants to read a litany of dry facts, names, and dates—especially in something as personal as a family history.

The wonder of family history, what makes it different from every other form of writing, is its power to connect living family members to those who came before them.

To make those connections—the ones that help us identify with our ancestors—we need to see that they were as human as we are. That means understanding their temperaments, quirks, and workaday habits; their responses to wins and losses; and the kinds of choices they made and why they made them.

In short, we need the writer to show us their personalities so we can relate to them—or, in some cases, understand why we wouldn’t have wanted to!

Great Family History Books Aren’t About Perfect People

“Perfect” people are boring. Besides, they don’t exist. They never have, and that includes our family members.

Idealizing characters makes them flat and renders a story incomplete.

People are complex, so it’s simply not accurate to write about real individuals as if they were as perfect as Pollyanna, Eleanor H. Porter’s impossibly bubbly character—so perfect she became a cliché!

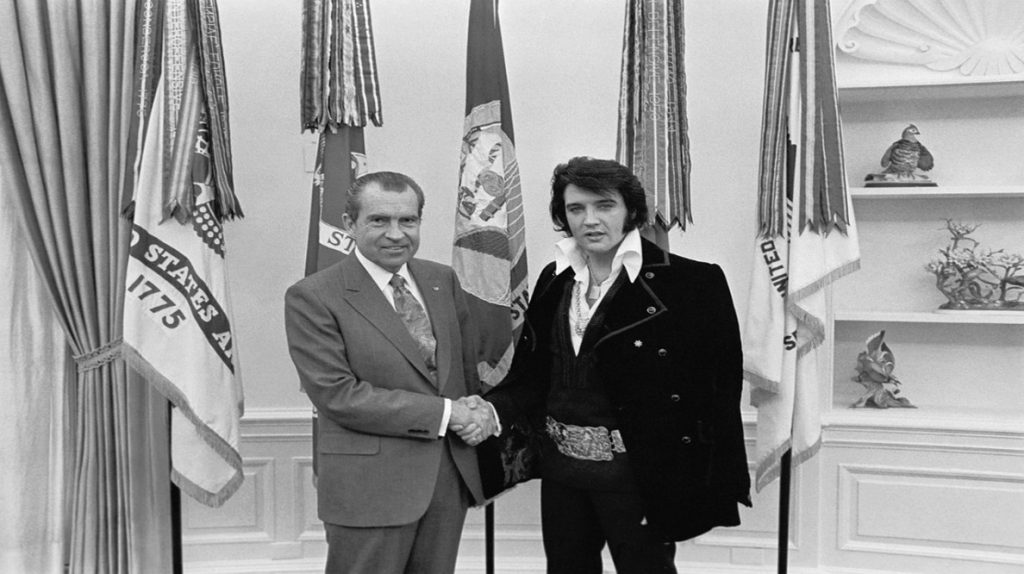

Consider instead the real life of President Richard M. Nixon, a complex story told in multiple biographies.

After losing presidential and gubernatorial races in 1960 and 1962, Nixon came back to win the presidency in both 1968 and 1972. His second term, however, ended when he resigned in the face of looming impeachment over the Watergate scandal.

Still, many of Nixon’s actions as president were laudable.

He founded the Environmental Protection Agency, launched the “war on cancer,” spearheaded the desegregation of schools in the South, and signed the Paris Peace Accords to end the Vietnam War.

When we read about the characters who make up a family’s history, we expect physical descriptions, but we know the heart of the story lies in the personalities it sketches—their seriousness or humor, laziness or diligence, tact or frankness, morals or lack thereof—all the complexities and contradictions that define human beings.

The Best Ancestry Books Meld Description with Storytelling

Descriptions should serve the story. Stories are full of action, speech, and facial and body expressions. Make your tale move through actions that illustrate personalities.

Show values and priorities through your characters’ attitudes and responses. Rather than stating, “He was hard-headed,” show it: “He stubbornly refused to bargain with buyers about prices.”

Physical traits and personality are inseparable.

For instance, when describing a young Confederate soldier: “His thin frame in its worn gray uniform bent to stir the coals of the smoldering campfire, as if looking for a spark of hope.”

Physical descriptions should go beyond the basics—they should help tell the story. Instead of “She had hazel eyes,” consider “Her round, striking hazel eyes seemed almost perpetually surprised.”

If your uncle’s hair was wild and unkempt, include that detail alongside descriptions of his animated speech and gestures.

If your grandmother’s posture suggested refinement, depict her sitting gracefully at the head of the family table.

If a child’s sparkling eyes and grin suggested mischievousness, work that into a story about him slipping a frog into his sister’s bed.

Examine old family photos. Did their clothing suggest relaxed prosperity or a hardscrabble existence? Show that by describing elaborate parties and seaside vacations—or dawn-to-dusk labor and sparse furnishings.

Comparisons from Nature and the Power of Environments

Comparisons to nature can create vivid character portraits. Consider: “Nothing escaped Professor Smart’s hawkish, roving gaze. No whisper between students escaped his notice as he peered at them over his beak-like nose.”

A person’s physical and social environments profoundly shape their personality. The reverse is also true—the way they interact with those environments reveals character.

In Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ 1938 novel The Yearling, young Jody Baxter’s personality develops alongside his pet deer, Flag. The story, set in the 1870s North Florida backwoods, portrays Jody’s family struggling to survive amid palmettos, snakes, bears, and wolves. After a crop-destroying rainstorm, Jody is ultimately forced to kill Flag after the deer repeatedly eats their replanted corn. The novel’s unforgiving environment is inseparable from its characters’ personalities.

It’s important to remember that environments—both physical and social—change over time.

Whether describing rooms, buildings, towns, or roads, ensure accuracy by aligning your narrative with historical reality.

What historical period did this person live in?

How might the economy, laws, and politics have influenced their thinking and decisions?

How did those decisions impact future generations?

Researching these details creates a more authentic family history book.

Link Revealing Moments to Build a Family History Book

Rhonda Lauritzen of Family Tree Magazine advises that every story needs at least one character, an inciting incident, a conflict or problem, a theme, and a plot with a beginning, middle, and end.

In writing your family history book, you likely won’t recount every person’s entire life in exhaustive detail. Instead, write “cameos” that reveal character through words, responses, and actions at key moments in their life—whether pivotal decisions or everyday occurrences.

Make these scenes rich with sensory details: sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures. How did they interact with material objects? Did they slam a door in anger or close it softly to leave unnoticed? Did they have a favorite mug, and what was their drink of choice?

These moments can showcase a person’s interests, conflicts, loves, rivalries, illnesses, lessons learned, triumphs, or workaday habits.

Since readers relate to these universal experiences, structuring your cameos around them fosters emotional connection.

A family history will likely feature multiple people and their relationships. Using cameos rather than exhaustive biographies makes personalities stand out—without overwhelming your readers. Connect these moments with a narrative thread that carries the story forward.

Character Focus in Your Legacy Book

When organizing your book, you might dedicate sections or chapters to individual family members, or structure the entire book around a central character, introducing others as they relate to that person.

Who’s the main character of your family’s story? Whose life best distills the family’s character, mission, or philosophy?

What made them someone the family identifies with? Did they start businesses, clubs, or associations? What kinds of expressions did they use? What type of spouse or parent were they? Were they generous? Charismatic? Fun? Brilliant? Well known?

Of course, not every family member was a saint.

If one relative was infamous for a bad temper or a stint in jail, include scenes that provide insight into the reasons behind their behavior—and highlight any redeeming qualities they possessed.

Hardly anyone is all bad. Even Ebenezer Scrooge had reasons for his miserliness, rooted in his father’s resentment and lonely boarding school upbringing.

Should You Hire a Ghostwriter for Your Family History Book?

Don’t let a lack of time or writing skills prevent you from preserving your family’s journey. Family history ghostwriters specialize in this type of writing.

A skilled ghostwriter listens to you and your relatives, conducts necessary research, communicates progress updates, and incorporates your feedback.

A ghostwritten family history book remains your book. You originate the concept, provide information through interviews, and make decisions about structure, content, and illustrations.

Your name appears on the cover, ensuring the book becomes a cherished heirloom passed down through generations—a treasure for your family and a valuable historical resource for others.